Black Canadians and HIV: Why Are the Most Affected?

Afro Biz • January 1, 2020

World AIDS Day on Dec. 1 marks a critical stage in the Canadian response to HIV. Decision-makers are proposing to end HIV transmission nationally and in Toronto in the next five to 10 years, based on recent innovations in HIV treatment and prevention. However, there is a great deal of uncertainty about how the promise of ending HIV will materialize for Black Canadians.

The new technologies include a combination of drugs – pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP – that substantially reduces the chances of at-risk individuals acquiring HIV. Moreover, people who are living with HIV and maintaining their medically prescribed drug regimen may achieve viral suppression, which means that the chance of transmitting HIV to a sex partner is negligible.

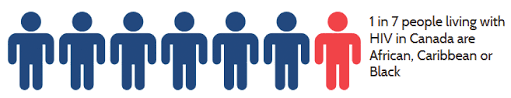

According to the health authorities that monitor HIV in Canada and Ontario, for the last 20 years Black communities have carried a hugely disproportionate burden of HIV.

In 2017 Black people accounted for 25 per cent of reported HIV cases in Canada, which is far in excess of the Black share of Canada’s population (3.5 per cent). The trend is similar in Ontario, where Black people make up 5 per cent of the population but accounted for one-quarter of new diagnoses.

In contrast, white people make up almost three-quarters of Canada’s population, but only 35 per cent of reported cases of HIV in 2017. Similarly in Ontario, white people accounted 72 per cent of the province’s population in 2016, but barely half of new diagnoses 2012-2017. In other words, the benefits of HIV prevention have accrued mainly to white Canadians.

Black people endure numerous inequities that, cumulatively, make them particularly vulnerable to HIV. Compared to white people, Black people are more likely to experience household food insecurity, inequity in the criminal justice system, and discriminatory treatment in education.

In addition, Black people are more likely to live in poor neighbourhoods, be unemployed or under-employed, and earn less income. Yet, plans to address or end HIV transmission in Canada elide racism and the systemic disadvantage that undermine Black people’s health and wellbeing.

One of the main tools to track the impending end of HIV is the engagement cascade. This approach says that Toronto, and Canada too, will be on track to end HIV when 90 per cent of people who are living with HIV are diagnosed, and 90 per cent of the diagnosed are on treatment, and 90 per cent of those on treatment have the virus suppressed.

This scheme still leaves behind 30 per cent of people who may be unaware of their infection, have unstable access to care and treatment, and are struggling with poor outcomes. But who will constitute the 30 per cent? Already, there is compelling evidence that Black people are falling off/out of the cascade.

In other words, at the end of HIV, Black people may be concentrated among the 30 per cent who are still struggling with the epidemic. Therefore, for whom will HIV end?

Unfortunately, Black people inhabit a Canadian social system that systematically undermines our claims to the rights and benefits of citizenship. Given this history, recent innovations in treatment and prevention may be inequitably available to Black communities. Also, there is evidence from elsewhere that people who are systemically disadvantaged are less likely to achieve or maintain viral suppression that is essential for ending HIV transmission.

Racism is not a mere inconvenience, so we must insist that the plans and strategies to end HIV transmission address (rather than reproduce) the systemic conditions that fundamentally disadvantage us as Black Canadians. Otherwise, the “end” of HIV transmission may be a disaster for Black people – resources that are currently available to address HIV will have been shifted elsewhere while Black people continue to shoulder the epidemic.

For Black people, current debates about ending HIV give us scope to press our case. We must seize opportunities to insert our ideas, demands and agenda into the various plans and proposals. We have a long way to go, but we must remain aware of what’s at stake and the seriousness of our situation.

Source: http://ow.ly/JeQY30q65Az